The Renaissance (1450 - 1600)

The trends and movements of referring back to Antiquity that came to be 'the Renaissance'

flourished in the Mediterranean especially and spread from there over the Western hemisphere. The Renaissance is generally dated to have begun around the 1500s in Northern Europe, although in

Italy it dawned even in the early 1300s with the outstanding frescoes of Giotto and the beginning of scholarship into ancient knowledge.

As time is fluid, dividing time into eras is contested in (art) historical research. As a rule, however, dating the beginning of the Renaissance to 1500 for Northern Europe and 1450 south of the Alps is generally accepted.

Culturally, it was a golden age dominated by increasing wealth through international textile and banking networks, rising manufacturing, art patronage and scientific progress. Florence was a major hub of Renaissance activity, ruled by the immensely rich Medici family who had acquired their wealth through banking and cloth trade. The names of Italian artists of those days are still extremely famous, e.g. Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarotti, Fillipo Lippi and Sandro Botticelli, just to name a few. Lesser known but very significant artists are, for example, Domenico Ghirlandaio who captured scenes of the everyday-life in his works.

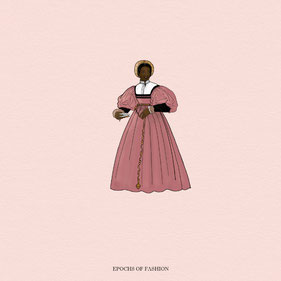

Renaissance dress is, like dress of all eras, complex and very varied depending on the wearer's social status, fortunes, and place of habitation. Everyone wore a linen shift under their clothes,

regardless of whether these outer layers were very lavish or rather plain. In outerwear, the materials were still the same as in the medieval era, that is to say natural fibres such as linen,

wool and silk. Gowns are no longer cut as one-pieces but have a waist seam that divides their construction into bodice and skirt.

Women's gowns are generally floor-long and have full skirts. Sleeves are generally detachable so that they could be exchanged between different dresses. This meant that there was a) the opportunity to mix up one's clothing and b) the chance to save some money by having fewer pairs of sleeves than gowns. Clothing is still extremely precious in the Renaissance and households spent as much as a quarter of their annual income on cloth and tailoring services. The women in families were skilled at needlework but clothing was not generally made in the home but commissioned from specialised dressmakers. Only the sewing of linen shifts, alterations and mending were generally done in the home. Sumptuary laws still restricted what styles, cloths and colours people of each rank and profession could wear. This regulated, for example, who could wear mink fur as opposed to rabbit fur.

Renaissance styles In different places

1. Venice:

The fine gowns of these two Venetian Ladies are very high-waisted. The two are apparently prosperous – pearls are stitched around their low necklines. The lady in yellow wears a necklace of big pears and the other a heavy silver one. Gold threat is worked in the fabric of the sleeves of the woman playing with the dog and her hem is decorated with golden braid. The lady in yellow has a hem edged with a silver saw-toothed braiding. They indulge in the fashion of slashing, the sleeves have huge cut-outs showing a puffy underdress. Three different ways of slashing can be seen in this painting: small slashes in the bodice of the lady in yellow, huge oval cut-outs in her sleeves and thirdly, the foreground ladies' sleeves which look like just ¾ of a sleeve with edges tied together with ribbons.

2. German-Speaking Lands:

The great Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach the Elder lived from about 1475 to October 16, 1553. The artist of German origin painted several women who are all wearing a distinctive style of dress. Basically, the elements of this style are

- a slim waist with the help of a tight bodice with a relatively low, square-cut neckline which bares a part of the shoulders, front lacing with black cord

-

sleeves that are slashed at several places/consist of several pieces which are connected

through a lacing and show the puffy undergarment [baragoni those decorative puffs in the upper sleeve are called]

- a wide skirt with organ-pipe pleats

- very colourful and ornamented attire

Two kinds of fabric dominate the gown: purple velvet (infrequently black) and gold brocade. The latter appears as braid along the neckline down to the waist, as ribbon on the sleeves and in three levels at the lower skirt. Approximately in the middle of the skirt the first and narrowest level is placed. The next level, twice as broad, is located at about a quarter of the skirts length over the hem. The broadest, three time as wide as the narrowest, is at the hem. The measuring of the levels in whole-numbered multiples should create an air of harmony. When notional dividing the space from the front neckline down to the waist in two, the lower half is the lacing. One can see the white under-gown. The upper half is a rectangle of the same gold brocade or other fabric; usually gold or red, too, and embroidered with stitching and pearls (squiggled floral motives or geometric patterns like the diamond pattern). The back of these gowns is in general square-cut and relatively low.

Another style of the German lands was the Swabian Gown and the headdress called 'Wulsthaube'.

The gown is characterised by a V-neck with gathered pleats underneath over the belly. It has a full skirt and full, bell-shaped sleeves. It is worn over a linen shift, like all medieval and Renaissance garments.

The headdress is made from a stuffed tube of fabric attached to a cap. It is placed on the head and then covered with a fine linen cloth and other decoration such as brooches.

3. Florence, 1550s:

Eleanor de Toledo (ital. Eleonora di Toledo) was the wife of Cosimo I de'Medici. As her name suggests she was born in Toledo, a province in central Spain. In 1539, aged 17 years, she was married to the future ruler of Florence and brought an immense dowry with her. Her father, Vice-Roi of Spain, had tried to persuade Cosimo in vain to take the elder daughter with an even larger fortune as a wife. Cosimo, however, wanted to marry the younger Eleonora, whom he had seen some time before and liked well. It is reported that he remained faithful to her throughout their marriage.

Around the year 1545, Angolo Bronzino painted Eleanor and her son Giovanni. Eleanor is clad in a gown of voided velvet (velvet with satin background). Her sleeves in the

portrait with her son are quadratically in profile. Her sleeves consist each of four tapes of fabric held together by many gemmed little brooches to form a sleeve.

Accessories:

A popular accessory for Italian ladies was a fan to cool themselves in the summer heat. As folding fans were not yet invented, they used a flag or weathervane fan. These flag fans consist of a handle (wood/ebony, gold or silver) and a turnable flag of stiff material. One would make rotary moves with the hand and the fan spins and provides cool air. Fans made of feathers were used as well as can be seen in the portrait by Pieter de Kempeneer mentioned above. To protect the hands from the winter's cold muffs were used. Usually, they were made of black silk or velvet adorned with embroidery and lined with fur.

Shoes:

Usually, the delicate footwear of the ladies was hidden under heavy floor-long skirts. In the renaissance, the high heel became a fashionable attribute: in the year 1533, the small Caterina de'Medici, Princess of Urbino, came from Italy to France to marry the Duke of Orleans. She wore high heels to appear taller and many female members of the French Court soon copied this fashion (Italian heel). In the following time the women wore shoes with more than 10cm (8 inches) heels, quite similar to modern stilettos. In general, ladies wore delicate footwork suiting their feet. The cow-mouth-shoe, however, that had come up towards the end of the middle-ages was still in fashion.

By the end of the 15th century, another style of footwear had arisen: the so called Chopines. Those platform shoes had their origins in the pattens. The Chopines' soles were made of cork trimmed with fabric which, at their zenith, had a sole height up to 75cm (circa 30 inches). This fashion was most popular among patrician women in Venice and the higher the shoe, the higher the social rank of its wearer. With the consequence that the ladies needed up to two maids to balance along the streets.

Beauty:

A high forehead was considered an expression of prudence and consequently the front hair was removed (plucked or shaved). The hair line thus wandered up the head some centimetres. Fair hair was a beauty goal and brought women with darker hair outside, where they let the their hair bleach in the sunlight. For a short period of time a strawberry blond/ginger/auburn kind of tone was desired (called Titian red). These looks were supported/created by bleaching with, for example, chamomile or by using henna.

Hair:

The hairdos became increasingly elaborate and unique to each wearer. Generally, there were two primary styles: on the one hand, the curly hair was parted in the middle and fell down on the shoulders while the top layer of the hair was twisted into a bun at the back of the head [seen in Ghirlandaio's portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni]. On the other hand, there were the Roman inspired plaited/braided coiffures [seen in Botticelli´s "Simonetta Vespucci"].

Renaissance portraits show braids arranged in many, many ways and styles. Not seldom, hair-pieces had to be added as the own hair was not enough for

the opulent hairdos. Young (unmarried) women and girls wore their hair flowing loosely over their shoulders or twisted or braided with ribbons and pinned up. Curly hair, thanks to iron hair

curlers heated in the fire, was universally fashionable. The Balzo was an opulent headpiece which first came up in the early 15th century in Italy, looking much like a turban or a large

circle or half-moon around the head. It was made of wire, padding and hard-wearing linen like buckram, covered with precious fabrics, pearls, braid and fur.

To the “Saxon gown”, on the on hand a hairnet of gold and pearls can be worn. The other

variant is a great cap of red fabric called cap or Barett (alike to men's).

Eleanor de Toledo wears her hair in a hairnet decorated with pearls or gemstones. Hairnets, or

the less sheer hairbags, were major elements in Renaissance fashion for the head. On the one hand, they covered the hair decently (the hairbag) or at least kept it bundled. Adornment didn't stop

from them. Consequently, especially hairnets used to be decorated with silver or gold thread, pearls and gemstones. A variant is a hairnet or -bag sitting at the back of the head, held in place

by a ribbon or band around the forehead. To this, a long artificial plait (wrapped in fabric and interlaced with ornamental ribbons) is attached.

Jewellery:

The nobles and the increasingly rising middle class wore jewellery (except from the stylish aspect) to show their wealth.

Rings were very popular and several were worn on each hand. Astonishingly, looking at various renaissance portraits, you can see the pictured persons wearing rings not only third phalanx (like

today) but also on the second. Meanwhile this fashion is experiencing a revival in the so-called Midi-rings.

An interesting thing is the so called marriage pendant. This pendant made of gold

contained two gems above another – a blue one (diamond, the upper stone) and a red one (probably ruby, the lower one). Attached to the pendant which was worn on a silver or coral necklace are

three pearls. The latter necklace was believed to increase fertility.

In portraits of women wearing the “Saxon gown”, they are wearing huge gold chains, great golden

and gem-studded collars and finer golden necklaces.

The Ferronnière was a head ornament primarily fashionable in the 15th century in Italy. It consisted of a thin ribbon or thread (usually black) on which centrally a jewel was attached. This jewel was usually crafted of precious metal and studded with one or several gemstones and pearls. This jewel was placed centrally onto the forehead and the threads were run horizontally to the back of the head over the hair where they were affixed. An example of the ferronnière in art history is the portrait 'La Belle Ferronnière' from the school of Leonardo da Vinci (1490-6), or the Portrait of a Woman by Bartolomeo Veneto (historically said to be Lucrezia Borgia although contested by newer research).

Patterns:

- Burda 7171

- Butterick 4571 (dresses)

- McCall's 2806

- McCall's 4107 (Renaissance top with several sleeves)

- McCall's 5444

- Simplicity 5582

- Simplicity 7096

- Simplicity 7097

-

Simplicity 8735 (Italian style Renaissanc dresses; out of print)

-

Simplicity 9531 (COSTUME COLLECTION) (Italian style dresses; high-waisted and puffed

sleeves)

- Please note that this list claims no completeness and does not operate as advertisement. It was merely composed for informative purposes. Furthermore, no valuation of the patterns is implied or intended -

© Epochs of Fashion